Story & Photography by Jason McDowell (@cessnateur)

The 1980s were a fun time. The decade brought forth a frenzy of computerization and a wild enthusiasm for technology of all types. The Star Wars franchise was in full swing, home computing and video gaming were exploding in popularity, and lasers were influencing everything from car names to children’s toys.

The aviation industry wasn’t immune to this technological mania. Composite airframe technology was transitioning from small, experimental aircraft to military fighter jets and larger passenger aircraft, and CRT displays were quickly replacing physical “steam gauges” on instrument panels.

A small handful of manufacturers and investors went all in on this emerging technology, betting that private and corporate customers would become attracted to their unique combination of composite airframes, unconventional canard wing configurations, and fuel-efficient turboprop powerplants.

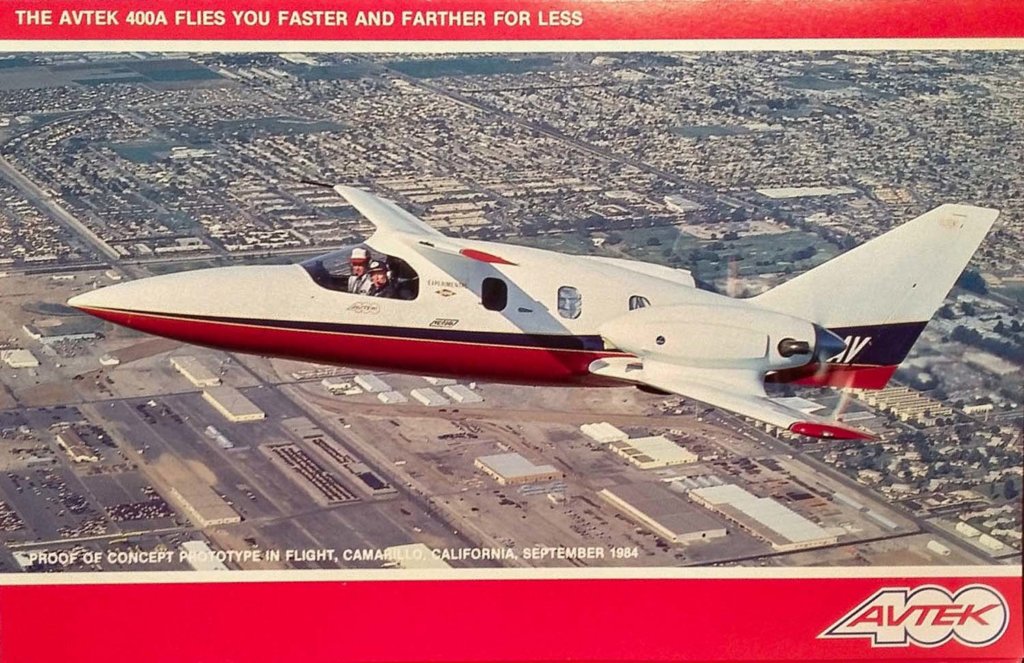

The Avtek 400A was among the first when it took flight in September of 1984.

With its sights set squarely on the traditionally configured Cessna Conquest, Piper Cheyenne, and Beechcraft King-Air 90, the Avtek embraced advanced composites, which were used to mold the fuselage into a more flowing, organic shape than its aluminum counterparts. KEVLAR and NOMEX brand names were emblazoned on the side of the fuselage and sprinkled throughout their brochures in all caps, emphasizing the use of cutting-edge technologies in the airframe.

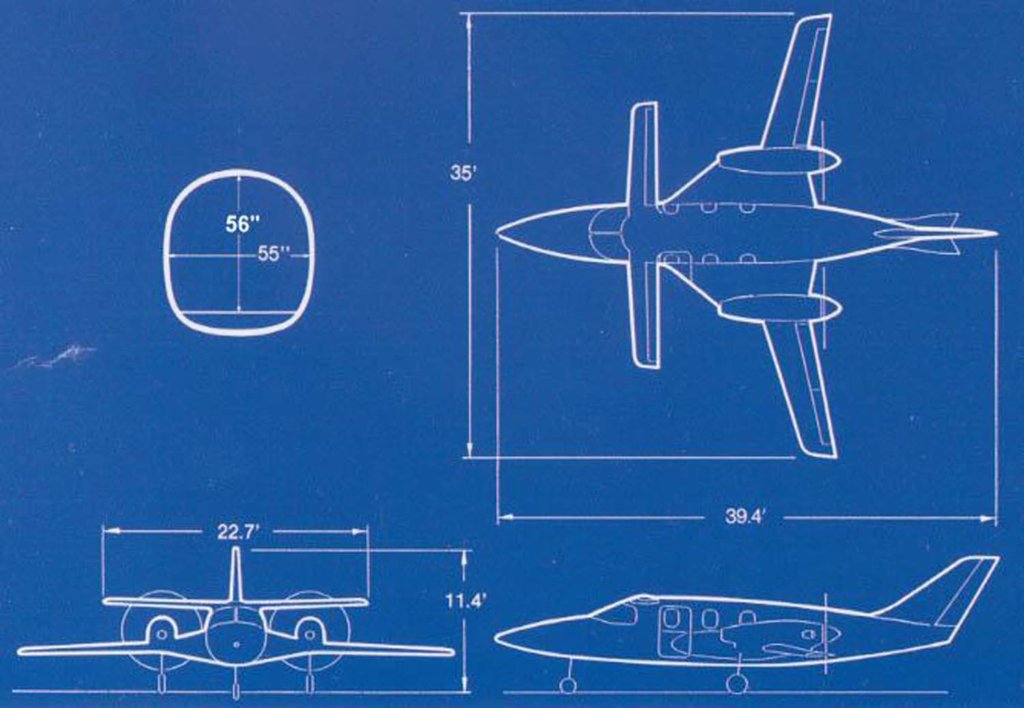

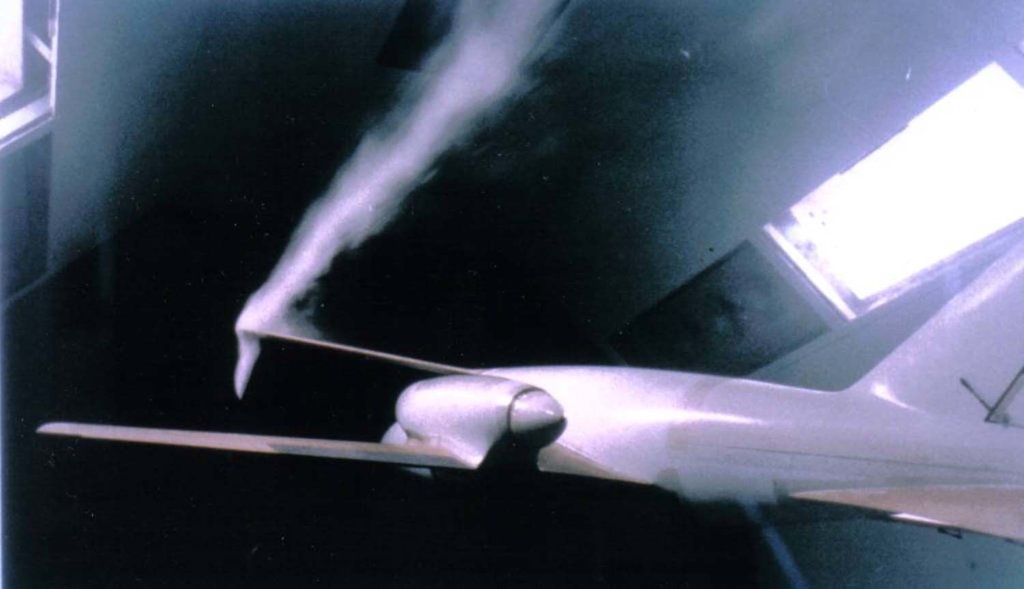

The striking canard configuration – using a small forward wing in place of a rear horizontal stabilizer – brought with it various claims of superiority, as did the unconventional pusher engines, which placed the propellers behind the engine rather than ahead.

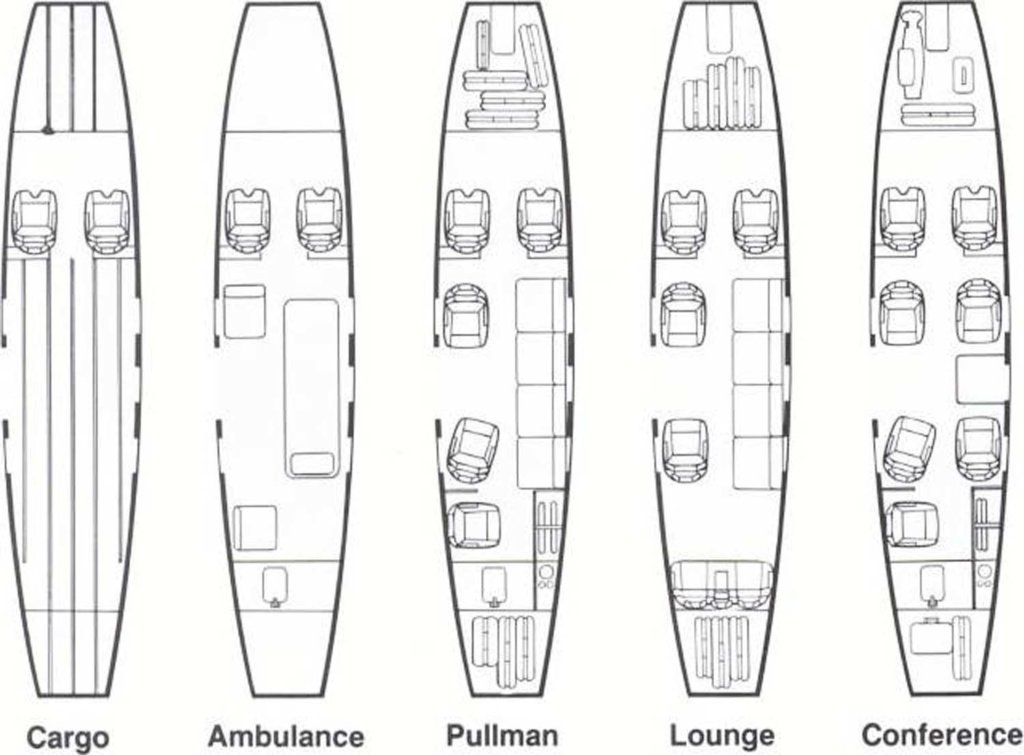

Among the numerous benefits cited, the resulting design was said to reduce the cabin noise level, increase interior space and lower drag to provide a level of efficiency above and beyond that of any competing aircraft.

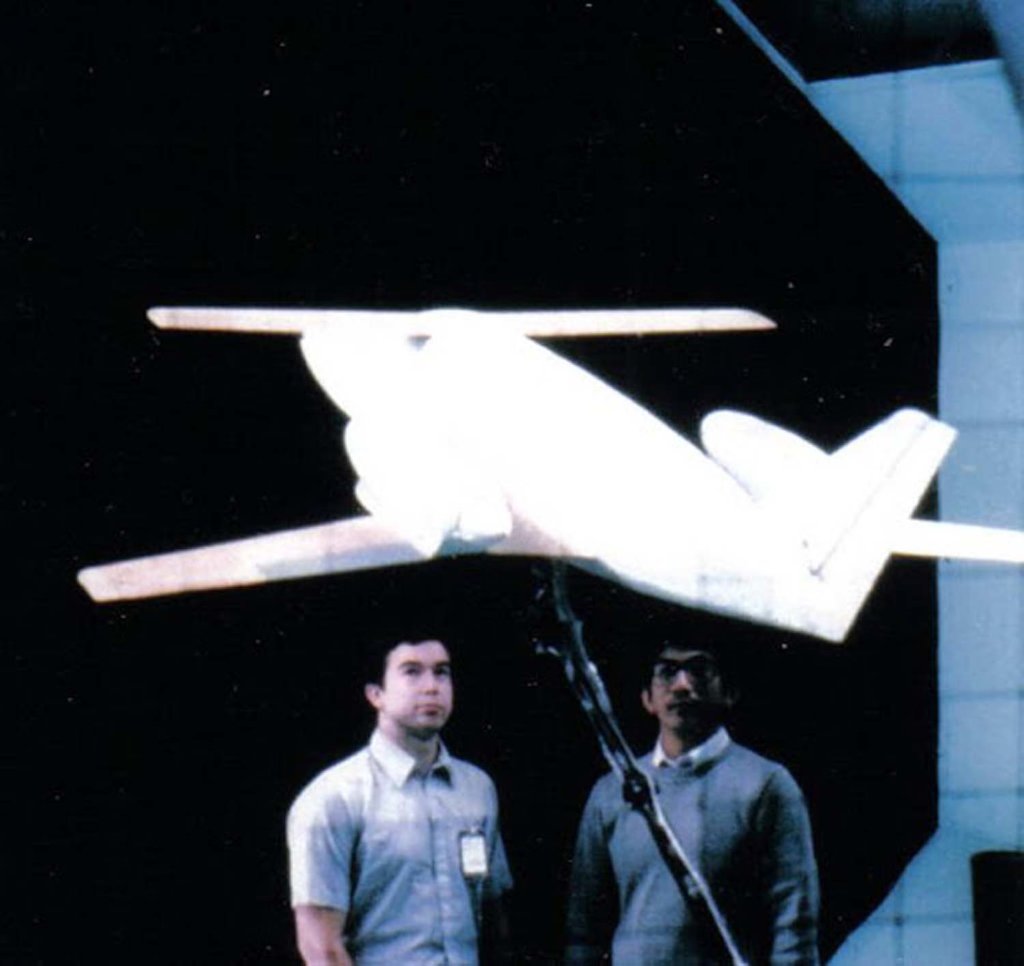

Indeed, the numbers demonstrated by the Proof of Concept (POC) aircraft were impressive. With twin 680-horsepower Pratt & Whitney PT6A-3 engines, it could fly as fast as 352 knots and as far as 2,400 statute miles (3,862 km). These numbers bested most traditional turboprops from Cessna, Piper and Beechcraft by a wide margin, as did its service ceiling of 41,000 feet (12,497 m) and claimed fuel efficiency of 10 miles per gallon.

Avtek’s marketing efforts were nearly as impressive as the aircraft’s performance. In November of 1985, the aircraft appeared as the fictional “Stappleford X-400” in the third season of the “Airwolf” television series, where it performed in a low level “dogfight” as its fictional machine guns blazed.

Of course, building the aircraft and producing the initial performance specs is one thing; achieving FAA certification and bringing it to production is quite another.

And this, like so many other failed aviation endeavors, is where the Avtek’s momentum came to a stumbling end. As the old adage goes, “the quickest way to make a million bucks in the aviation industry is to start with a billion.” As the company’s development costs increased, the investment dollars decreased.

Those companies with deep pockets moved forward – First Beechcraft with its Starship, and later, Piaggio with its Avanti. Both of these employed canard wing configurations, and both used Pratt & Whitney PT6 turboprops.

Opting to use proven, comparatively inexpensive aluminum for its airframe, Piaggio went on to build 236 Avantis. But the time and capital required to develop and certify an airframe constructed out of newly emerging composites created a nightmare for Beechcraft, and only 53 Starships were built. Those 53 came up high in weight and short in performance, as Beechcraft was forced to “overbuild” the airframes to satisfy the FAA’s cautious skepticism.

As Beechcraft and Piaggio spent the 1990s manufacturing and selling their canard aircraft, the sole Avtek sat baking and deteriorating in the California sun, unprotected on a remote ramp at Camarillo Airport. Ultimately, the Avtek Corporation declared bankruptcy in 1998.

In the early 2000s, the company’s assets, including the aircraft itself, were sold to a new company called AvtekAir. While this initially bode well for the future of the aircraft, no apparent progress has been made. The Avtek remains deteriorating in the elements, as does the new company’s website. Optimized for Netscape 7, the site today describes AvtekAir as “a research and development company to design and certify the first advanced composite, turbine-powered business aircraft,” apparently unaware that this title had long ago been claimed.

Today, composite airframes are commonplace among aircraft manufacturers. The construction methods and processes have been refined over the decades, and the government entities responsible for certification are no longer as averse to the technology as they once were. While the journey from concept to certification remains lengthy and expensive, today’s airframe manufacturers enjoy a relatively smooth ride as they proceed atop the foundation built by their predecessors.

With any luck, the sole Avtek 400A will someday be saved from the harsh California sunlight and UV rays. Perhaps it will be donated to a museum where it can be preserved and displayed to future generations of aviation enthusiasts. Particularly those who might not have been around to appreciate the era of emerging technology in which it was created.

Jason McDowell is a writer and photographer specializing in aircraft design and aviation history. He is the author of the @cessnateur Instagram feed and also contributes to FLYING magazine.